The following excerpt is from a lecture I gave at the Brooklyn Public Library.

I am, like many in this community, a twofold nerd. I love both science and popular culture. I am equally engaged learning about the physics of light as I am watching Star Wars. So it is not surprising that while thinking about one, I found correlations with the other.

There are two types of color mixing, additive and subtractive. The former concerns the combination of lights, while the latter involves mixing paints.

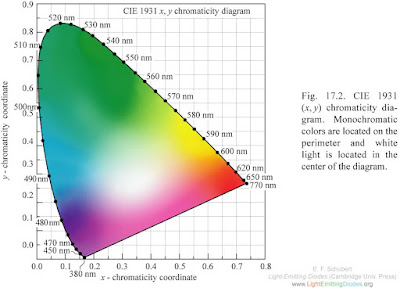

If I am painting a Star Wars illustration, something classic like Luke vs. Vader, I need to know what it will look like when their green and red lightsabers collide. Fortunately for me, the International Commission on Illumination anticipated my predicament back in 1931. They created the CIE (their French acronym) chromaticity diagram, a Cartesian representation of all possible colors.

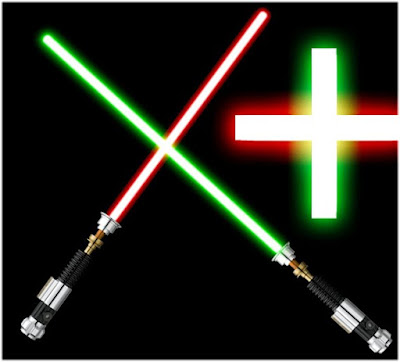

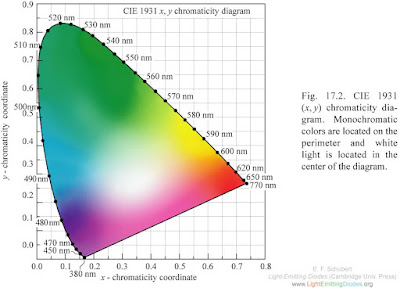

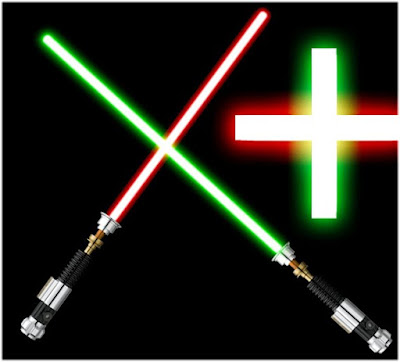

The data is derived through the painstaking recording of people’s individual responses to colors, which are then averaged. This information is then correlated through mathematical transformations so that the geometry reveals precise relationships. Specifically, one can discover the mixture of any two colored lights by drawing a line between them. When extended from red to green, the midpoint of the connecting line yields yellow, and we have our answer.

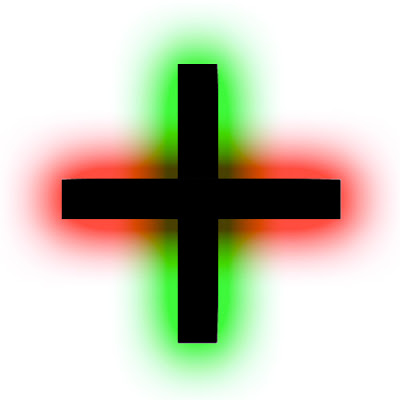

What about subtractive color mixing? For that we must imagine a new kind of weapon, the darksaber. The darksaber absorbs all light into the blade, but is surrounded by a cloud of ink that absorbs all light, save one frequency or hue.

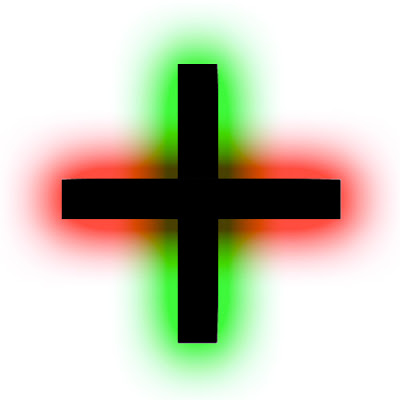

If two darksabers come into contact with each other, the resultant mixture is always darker than either component. A red blade and a green blade would produce a dark brownish gray.

This dichotomy lies at the heart of representational painting. The painter attempts to recreate a world of additive color using a subtractive process. This is one reason why painting in Photoshop comes easier to most. You are literally painting with light, so the relationship between subject and medium is direct and intuitive. But in the real world, the brush is, essentially, a darksaber operating in lightsaber country. The laws are foreign, but they can be translated.

I am, like many in this community, a twofold nerd. I love both science and popular culture. I am equally engaged learning about the physics of light as I am watching Star Wars. So it is not surprising that while thinking about one, I found correlations with the other.

There are two types of color mixing, additive and subtractive. The former concerns the combination of lights, while the latter involves mixing paints.

If I am painting a Star Wars illustration, something classic like Luke vs. Vader, I need to know what it will look like when their green and red lightsabers collide. Fortunately for me, the International Commission on Illumination anticipated my predicament back in 1931. They created the CIE (their French acronym) chromaticity diagram, a Cartesian representation of all possible colors.

The data is derived through the painstaking recording of people’s individual responses to colors, which are then averaged. This information is then correlated through mathematical transformations so that the geometry reveals precise relationships. Specifically, one can discover the mixture of any two colored lights by drawing a line between them. When extended from red to green, the midpoint of the connecting line yields yellow, and we have our answer.

What about subtractive color mixing? For that we must imagine a new kind of weapon, the darksaber. The darksaber absorbs all light into the blade, but is surrounded by a cloud of ink that absorbs all light, save one frequency or hue.

If two darksabers come into contact with each other, the resultant mixture is always darker than either component. A red blade and a green blade would produce a dark brownish gray.

This dichotomy lies at the heart of representational painting. The painter attempts to recreate a world of additive color using a subtractive process. This is one reason why painting in Photoshop comes easier to most. You are literally painting with light, so the relationship between subject and medium is direct and intuitive. But in the real world, the brush is, essentially, a darksaber operating in lightsaber country. The laws are foreign, but they can be translated.

you just blew my mind.

ReplyDeleteReally though great post, I think about this relationship a lot and you have given some LIGHT on understanding it better.

gonna think about it and read this post again about ten times before i give a real comment....

ReplyDeleteBTW, for me it´s easy to paint traditionaly then digitaly...

now i just need to build that dark lightsaber

ReplyDeleteThat's a great AND fun writze up.

ReplyDeleteI love the idea of thinking about that.

This... is amazing. And couldn't have come at a better time, I may be doing a lightsaber piece in the near future. Thanks for the knowledge drop!

ReplyDelete